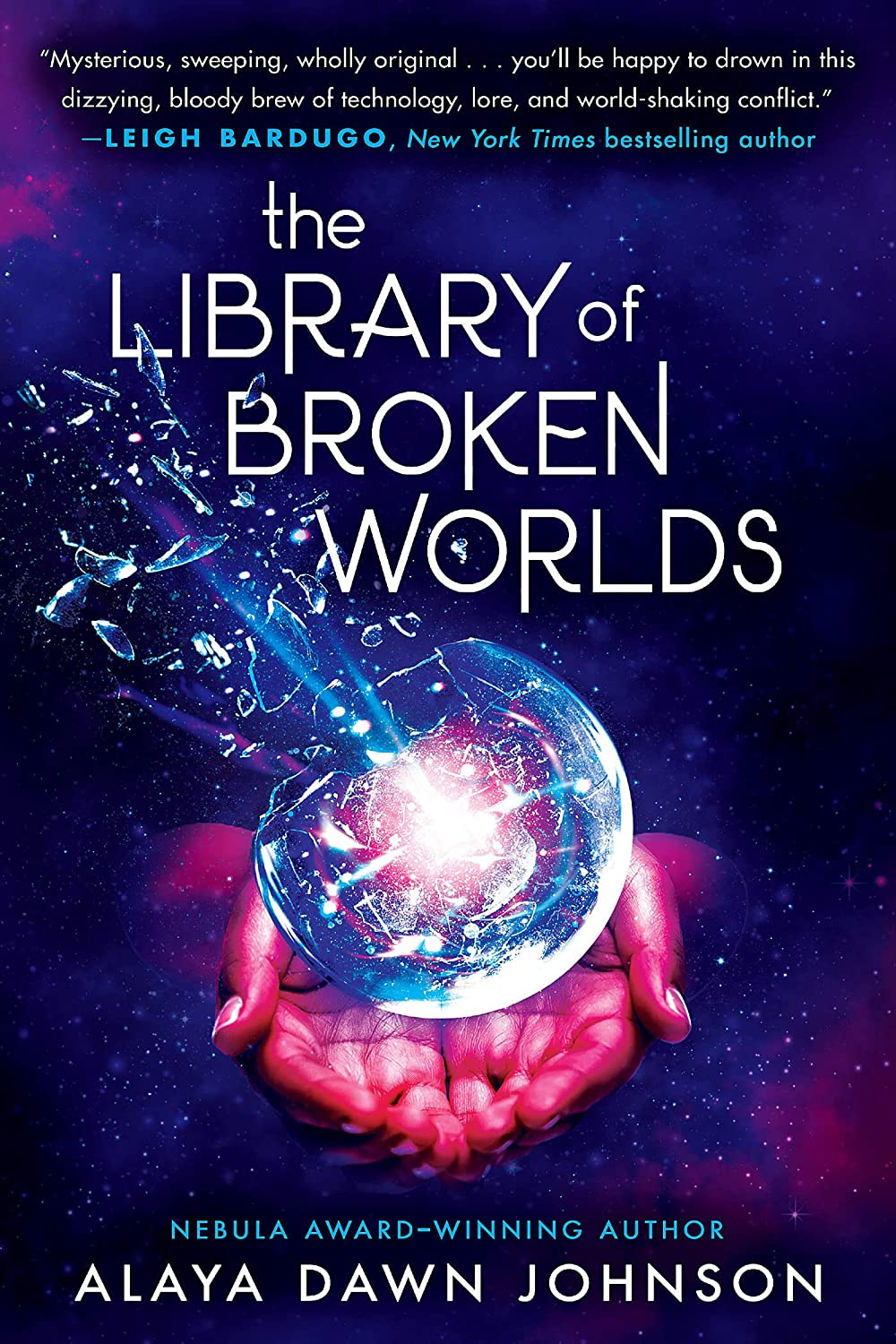

Alaya Dawn Johnson’s Broken World Library Is The Library You’ve Never Visited

In decades of reading SFF, I’ve never encountered a world quite like the library in Alaya Dawn Johnson’s Library of Broken Worlds. Some things about it are familiar, though it would be rude to reveal the most important aspects of it. But most of it came out of Johnson’s head the way Athena came out of Zeus’ head, and I’m making this divine comparison on purpose because the library is full of gods.

But these gods – the material gods – are not like the names we know from ancient mythology. They have avatars, personalities; librarians can communicate with them in various non-metaphorical ways. Librarians don’t use Space Google (did I mention libraries are in Space?), although they do have some basic query tools. Instead, they delve into the library to connect spiritually with the gods, seeking answers to extremely important questions. One of them concerns whether a culture can claim the right to murder others.

Many of these issues involve a girl named Freida, who was born in a library and, at the beginning of Johnson’s rich, layered, powerful book, is on a mission to kill the oldest, most bloodthirsty substance God.

First, though, they had a conversation.

It is no exaggeration to say that I have been waiting for this book for at least nine years. Not that book, exactly, but a new teen book by Johnson, whose 2013 The Summer Prince, despite being shortlisted for the National Book Award, still seems to be getting too much attention. (Her latest coming-of-age novel, Saints in Trouble, won the 2021 World Fantasy Award.) The post-apocalyptic future of The Summer Prince takes place in a hauntingly imaginative setting filled with art, love, and passion. Death, culture, and conflict, nuance.

These things and more drive the story of The Library of the Broken World, a book that requires both an in-depth spoiler assessment, teasing out the many clues woven into the bright cloth, and reading without any expectations. (I’ll avoid spoilers since it was just released.) In a way, I’m not entirely sure, “The Broken World” feels like the teenage cousin of Simon Jimenez’s “Spear Into the Water”; There isn’t that much in the form of a story, but there are many layers of myth, lies, and family within the story, all of which challenge you to separate the personal from the political, the spiritual from the practical.

What if there are gods, but there are also hypercubes? (These are more Engel than Marvel, but also entirely their own.) If humans exist in space, their worst tendencies — domination and power grabbing — are with us, even if other planets, other worlds also appeared, so what? What exactly is artificial intelligence? (I don’t really mean chatbots.) What is Destiny? What is love and family? How do people start their families or separate from those who hurt them?

The Shattered World Library is the story Freida tells the Namanites about her need to destroy the god. But she too is devastated, ravaged by the virus in her body when she communicates with the bull god of Maham, a world dominator with a small moon full of dissidents known as Miuri. On the other side of the galaxy is the world of Averu, described by one character as “the guardian of the peace, the elder, the creator of the gods.” The galaxies where Tira, Mars, the Sun, and the Moon reside form the other point of the triangle. The library sits in the middle and remains quiet. Hypercubes allow instantaneous travel between worlds, although each hypercube is controlled by only one of the worlds it touches.

Found in the library tunnels as an infant, Freida caused some controversy among the librarians, whom she wished to join. Is she alone? Is she a program? Was she created by God? What is she? Nadi, the librarian, finds her and treats her like her own child; Quinn plots against Nadi’s status, treating her like a thing.

Freida has even more reason to distrust Quinn, who is attacked by Quinn’s nephew early in her story. This happens in “Nanodrops,” a virtual reality experience that Freida doesn’t know how to make sense of, describe, or categorize. If it’s just happening in her head, is it true? Does it matter when it feels real? She kept it a secret, even from Nadi, and as she grew and learned, slowly moving toward a first love, then a second, the trauma seared deep into her bones.

The stories Freida told Nameren were about people she loved and how she helped or tried to help two people she loved find solutions to problems that were truly life-or-death. Joshua, from Dela, is trying to win a complex legal battle over his people’s rights to their homeland. (The author’s note notes that Johnson does not represent any “modern human culture,” but rather draws from a variety of sources for inspiration.) And then there’s Tav, a boy from Averu who is struggling to find his place in the world and escape the shadow of his famous father.

As Freida navigates these complex relationships and their accompanying challenges, she also grapples with the question of whether violence can ever be justified, even in the face of oppression and injustice. This is a weighty, thought-provoking theme that Johnson handles with grace and nuance, never shying away from the difficult questions but also never offering easy answers.

In the end, The Library of the Broken Worlds is a rich and rewarding read, full of complex characters, intricate worldbuilding, and thought-provoking themes. It’s the kind of book that rewards close attention and multiple readings, as there are always new layers to uncover and new connections to make. If you’re looking for a challenging and rewarding work of speculative fiction, this is definitely a book worth checking out.

Tagged "The Light at the End of the World", Historical Fiction, nationalism, Siddhartha Deb, social upheaval